Ishpadinaa Walking Tour ❋ Cason Sharpe

Let’s start outside the 7-Eleven on the northeast corner of College and Spadina. Take a look around. What do you notice? Likely the intersection is busy, teeming with children from the nearby elementary school, students from the nearby university, people going to or from work, carrying briefcases or bundles of fresh veggies, walking, driving, riding bikes. You might notice the shallow grooves created by the grid of streetcar tracks on the road, or the web of streetcar wires overhead. Do you see any pigeons? Have you looked at the 7-Eleven entrance yet? Is someone standing there by the door or seated on the ground? Consider asking them how they’re doing, or putting a few coins in their cup.

Welcome to Ishpadinaa, otherwise known as Spadina Avenue, an expansive promenade nearly fifty metres wide. The street takes its name from the estate of William Baldwin, a politician living in what settlers once referred to as Upper Canada in the 19th century. The word Spadina is an Anglicization of the Anishinaabemowin word Ishpadinaa, meaning high hill or ridge. The name Spadina refers to property, a naming practice steeped in the settler-colonial tradition of ownership. The word “Spadina” tells us little about the land we’re on, other than its connection to Baldwin's legacy. Ishpadinaa, however, refers directly to the land. The name identifies a specific topography, one that shapes the area in such an obviously fundamental way that it might be easy to overlook. Mishuana Goeman argues that a conceptual shift from property to land “is a powerful mechanism in resisting imperial geographies that order time and space in hierarchies that erase and bury Indigenous connections to place and anesthetizes settler-colonial histories.” One way to facilitate the shift from property (Spadina) to land (Ishpadinaa) is through a recognition of an embodied experience. From the entrance of the 7-Eleven, face south toward the Burger King across the street. Notice how the street slopes subtly downward? That downward slope continues all the way to the waters of Lake Ontario. Ishpadinaa is a hill. You’re currently standing about halfway up.

This hill has become a central thoroughfare in Toronto, a city constructed upon the traditional lands of several Indigenous nations including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishnabeg, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat peoples. “To be in good relationship with one another requires a critical conscious awareness and an acknowledgment of whose traditional lands we are now on as well as the historical and contemporary realities of those relationships,” writes Sandra Styres. I’ve been considering my own relationship to this land, as a Black settler born and raised a stone’s throw away from the hill you are currently standing on. What ongoing processes of colonization, capital development, displacement, land theft, and various free and forced migrations have led me here, to the street I’ve walked up and down countless times since I was a child, the land under my feet so familiar I often forget that it’s there?

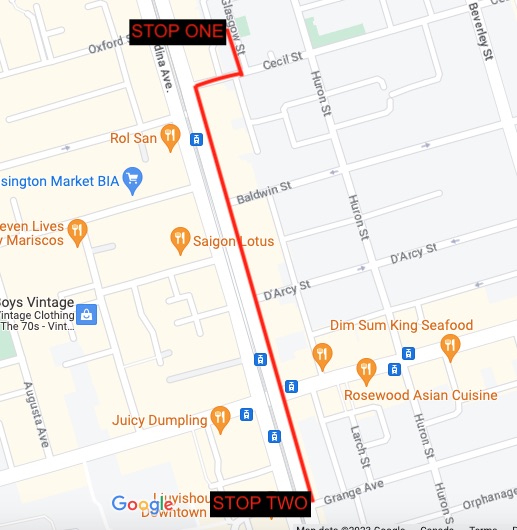

The tour will take about half an hour, depending on your pace. To get to our first stop, travel south down Ishpadinaa to Cecil Street. On your right you’ll notice Grossman’s Tavern, a popular blues bar where my father, a jazz musician, was known to take the stage on warm summer evenings. On your left you’ll see the Cecil Community Centre, built in 1890, which over the years has been reborn as a synagogue, a catholic church, a rec centre, a voting station, a community non-profit, and the venue of my older sister’s wedding. Take a left on Cecil to Glasgow Street, and then walk north until you reach the Glasgow Street Parkette.

STOP ONE: Unofficial Commemorative Bench

We’ve arrived at the Glasgow Street Parkette, the first stop on our tour. The parkette is tucked away just off Ishpadinaa in a narrow laneway with a strip of two-storey row houses along its western side. Constructed in the early 19th century, these row houses were once a part of the city’s Jewish settlement and are now home to many first and second generation Chinese settlers. Take in your surroundings. What do you see? Maybe the street is quiet save for the sound of the occasional bird chirp, or maybe you can hear the ambient noise of a bustling city. Can you feel the incline of Ishpadinaa under your feet?

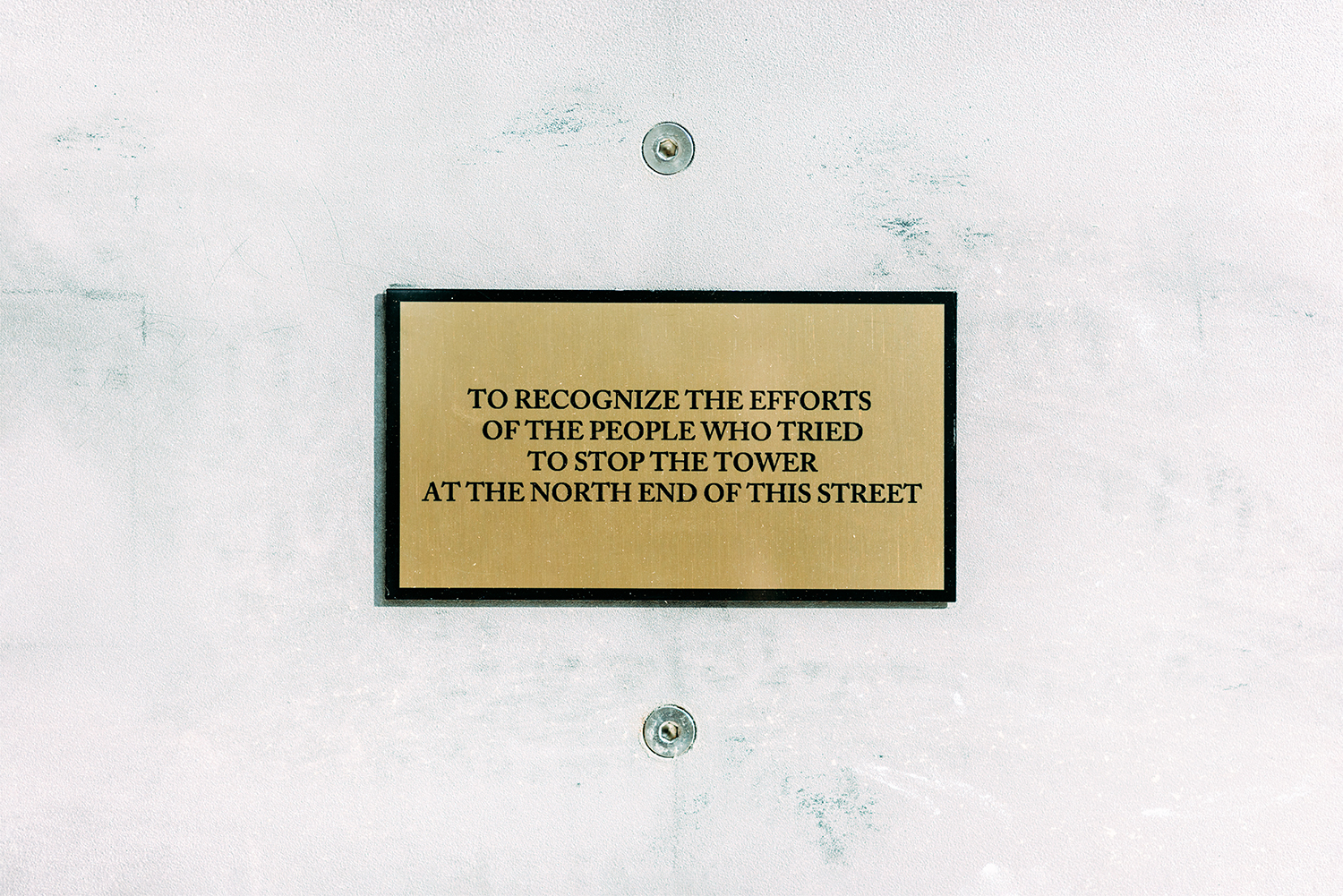

Approach the benches that surround the parkette’s southernmost planter. Do you see the two plaques installed there? You may recognize these kinds of plaques from various parks across the city. For a fee, the city will install them onto a bench or at the base of a tree to commemorate a lost loved one. The plaques in front of you, while easily mistakable for City of Toronto signage, are a site-specific art piece titled Unofficial Commemorative Bench (2021). Created by the artist Amy Lam, Unofficial Commemorative Bench mimics the form of an innocuous civic monument in order to pay tribute to the community activism of the residents of Glasgow Street. Engraved onto one of the plaques is the following message: 向曾經反抗 / 此街在北面的高樓發展的社區居民 / 致敬. The same message is engraved on the adjacent plaque, translated into English: TO RECOGNIZE THE EFFORTS / OF THE PEOPLE WHO TRIED / TO STOP THE TOWER / AT THE NORTH END OF THIS STREET (figure 1).

Do you see the tower at the north end of the street? Hard to ignore, isn’t it? The tower, a twenty-four storey privately owned student residence constructed in 2017, charges upwards of $1900 a month to rent a studio apartment without a kitchen. The residents of Glasgow Street, many of whom have lived in the neighbourhood for over 50 years, expressed concerns to the city that the height and the price of the tower would drastically alter the area they call home, but due to language barriers, a lack of community consultation, and state deference toward the capital interests of developers, they were unsuccessful in their attempt to prevent the tower’s construction. It’s the tallest building in the skyline at the moment, the entirety of Glasgow Street subsumed under its pall. Its presence imposes a particular story upon the land, a narrative where housing is only available to those who can pay a premium for it. Many residents in the city disagree with this narrative, although you wouldn’t know it looking at the skyline, which has become increasingly crowded with investment properties in which only the privileged few can afford to live. Take, for example, the townhouse where I grew up, a ten minute walk from here, which is currently in the process of being demolished to make room for a new luxury condo that will look strikingly similar to the one you see before you. The city I once knew has been overtaken by a sea of steel and glass, its history only reflected through plaques and monuments. Take a second to think of all the displacements—historical, contemporary, contested—that may have occurred throughout the city. How many have you seen commemorated? How many have been obscured? The challenge posed to private developers may not receive official civic recognition, but Lam’s subtle and cheeky intervention offers a counter narrative, a way to memorialize resistance amidst a rapidly changing horizon.

Figure 1. Amy Lam, Unofficial Commemorative Bench (2021).

To get to our next stop, go south on Glasgow to Cecil, and then take a left on Cecil, returning to Ishpadinaa. Walk south along Ishpadinaa. Pass the Japanese comic book store where I used to spend my weekends in middle school. Pass the LCBO where I used to buy Malibu Rum with my fake ID in high school. Pause at the corner of Ishpadinaa and D’arcy Street. As I write this, this corner consists of an empty lot under construction, but maybe by the time you take this tour, it will have been transformed into a new development. Cross Dundas, past souvenir shops and noodle houses, continuing south along Ishpadinaa until you arrive at Kai Wei Supermarket.

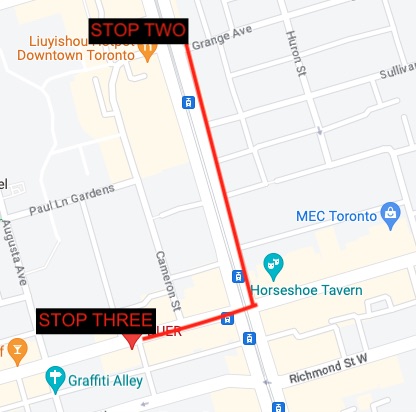

STOP TWO: Miss Canadiana’s Heritage and Cultural Walking Tours: The Grange

We’ve made it to Kai Wei Supermarket, the second stop on our tour. Located on the southeast side of Chinatown, Kai Wei is a vibrant market with some of the most affordable groceries in the city. Take a look around. Maybe duck around the corner, as I have, to avoid the crowd of midday shoppers. Keep track of how many different languages you hear. How much do seedless green grapes cost per pound these days? Can you name every fruit and veggie displayed on the sidewalk under Kai Wei’s faded red awning or are some of them unfamiliar to you? Lookout for any trees, plants, or wildlife that may have crept into the scene—perhaps a buzzing bee, or a mischievous raccoon if you’re lucky. Feel your feet planted on the ground, Ishpadinaa under you.

I’m not the first person to lead a walking tour through this particular intersection. Camille Turner took audiences to this very spot during her 2011 performance Miss Canadiana’s Heritage and Cultural Walking Tour: The Grange (figure 2). Hosted by Turner’s alter ego Miss Canadiana, a fictional Black beauty pageant winner, the performance walked audiences through Grange Park, a neighbourhood whose porous western border overlaps with the part of Chinatown where we currently stand. Focusing specifically on the area’s Black history, Turner’s tour examined the relationship between Blackness, colonial narrative, and land through storytelling, reenactment, and revisioning.

“My image as Miss Canadiana points to the contradiction of the Canadian mythology,” writes Turner. “My body, as a representation of Canadian heritage, is surprising only because Blackness is perceived as foreign in Canada.” By yoking this persona to a national identity, Turner upends racial assumptions of Canadian subjectivity that erase the historical and contemporary presence of Blackness on these lands. In a similar fashion, her tour challenges a colonial historical narrative that positions Canada as a safe haven for Black settlers escaping slavery in the United States by highlighting instances of legalized enslavement, racial violence, and discrimination that have happened right here in Toronto.

Consider, for example, Harry Gairey. Do you recognize that name? I didn’t know who he was until I watched an excerpt of Miss Canadiana’s Heritage and Cultural Walking Tour: The Grange on YouTube. Harry Gairey, a Black railroad porter, lived right here at this intersection when he first emigrated from Cuba in 1914. This is Gairey’s story, as told by Miss Canadiana, and now retold by me: in 1945, Gairey’s teenage son was denied entry to a skating rink that refused to serve Black patrons. An outraged Gairey took the incident to city hall, arguing that if young Black men could be conscripted into the military, they should have the right to skate wherever they wanted. The city enacted its first anti-discrimination ordinance two years later, thanks in large part to Gairey’s determined advocacy. There’s a skating rink named in his honour a few blocks west of here at Dundas and Bathurst. I learned how to skate on that rink, spent countless hours falling on my face without any knowledge of the man whose outspokenness made it possible for me to be there. Now anytime I pass Kai Wei Supermarket I thank Harry Gairey, not to mention Miss Canadiana for telling me his story.

Figure 2. Camille Turner, “Miss Canadiana Heritage and Culture Walking Tour” (2011).

To get to our third and final stop, continue south along Ishpadinaa, past Chinatown Centre, past the fabric and fur warehouses. Do you see that empty lot on the west side of Ishpadinaa, just north of Queen Street West, between the McDonald’s and the Alex Fur building? That used to be a Blockbuster, many years ago, where my sister and I would argue over rental choices almost weekly. Cross Queen Street West so you’re on the south side of the street, then walk west along Queen, past the roti and fried chicken shops, past the Cameron House, with the giant plaster ants crawling across its facade, until you reach McDougal Lane, right by the Circle K.

STOP THREE: The Bear Portraits (Cultural Revolution)

We’ve made it to the third and final stop on our tour. Tucked behind Queen Street West, the network of colourful laneways expanding before you is known as Graffiti Alley. Over the last decade or so, the site has become quite popular with tourists, aspiring photographers, and social media darlings. People visit from all over the city to snap pictures in front of its brick exteriors, which various artists have painted with intricate murals and overlapping tags. Take a look around you. Are there any photoshoots currently underway? I can smell the wafting scent of the nearby McDonald’s, and feel the land sloping downward a block away from Ishpadinaa.

Somewhere in or around these alleys, years before they became the coveted Instagram backdrops that they are today, the artist and photographer Jeff Thomas took a picture of his son Bear in front of a brick wall tagged with the words cultural revolution in thick black spray paint (figure 3). This small gesture, intended to archive a day downtown between father and son, became the first of The Bear Portraits (1984-ongoing), a series of photographs documenting Bear at various ages and in various locations including alleyways, streetcars, riverbanks, and in front of colonial monuments. “Looking at my seven-year-old son,” writes Thomas, explaining the genesis of the project, “I was reminded of what it was like for me as a young boy and my frustration with the fact that no one talked about what it was like to be an urban Indian. I wanted to alter that; to pave a way for him to be able to negotiate his Indigeneity within a culture of absence and invisibility.”

Mikinaak Migwans explains Thomas’s photographic interventions thusly: “He’s looking for the ‘missing Indian,’ right? So he’s going around, and through photography, he’s looking at all these public spaces. He’s looking for, like, ‘where am I in this? Where is my family? Where are the Native people whose land this is?’ And ultimately his point is that they have been disappeared from all this. It’s not that they’re not there; it’s that they’ve been disappeared.” The Bear Portraits expose this colonial disappearing and simultaneously resist it. Each photograph marks space like a graffiti tag, asserting Indigeneity within an urban landscape that actively attempts to remove it. The project’s ever-evolving nature challenges the colonial impulse to assign Indigeneity to a static past. As the series progresses, we witness Bear grow from boy to teenager to adult, his presence foregrounded in every image. Located in the present with an eye toward the future, The Bear Portraits are defiant and intimate in equal measure. Thomas began the series here, in these alleyways, although I don’t know exactly where. The cultural revolution tag has long since been removed or covered by the work of another artist, or perhaps the building where it was written has been demolished. But Thomas’s portrait remains as a record of the city as it once was, as well as the Indigenous communities that have always been here.

Figure 3. Jeff Thomas, “The Bear Portraits: Cultural Revolution,” (1984).

Much like Thomas and Bear, my father and I used to stroll these alleys on long and meandering Saturday afternoons. I wish I had some evidence to remember these strolls, but I had no idea that the landscape around me might one day change, so I never thought to document it. I’ve lived on or near Ishpadinaa for most of my life, but only recently have I begun to notice its geography and investigate its many histories. “Turning to cultural geographers who seek to discharge the notion of stagnant or normative colonial space is an important step in beginning the process of decolonizing space in settler states,” writes Mishuana Goeman. I hope this tour provides an example of what that process could look like.

From here I’ll let you go wherever you choose. Travel east to the Leslie Street Spit, west to the Humber River, or continue downhill along Ishpadinaa . As you walk, I encourage you to consider the land under your feet, the faces of the people you pass along the sidewalk, and the intersecting forces that have brought you to this hill. Is this your first time on Ishpadinaa, or have you walked this path before? What changes–social, natural, or infrastructural–have you noticed since the last time you were here? Keep walking, taking note of what you see, and in half an hour, you could be by the lake.

WORKS CITED

Cecil Community Centre, “About Cecil.” Accessed April 11, 2023, https://cecilcentre.ca/about/.

Goeman, Mishuana. “From Place to Territories and Back Again: Centering Storied Land in the Discussion of Indigenous Nation-Building,” International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies 1, No.1 (2008): 23-34.

Johnson, Jon. “Pathways to the Eighth Fire: Indigenous Knowledge and Storytelling in Toronto.” PhD diss., York University, 2015.

Lam, Amy. “Unofficial Commemorative Bench.” Accessed February 9 2023. https://www.gallerytpw.ca/amy-lam-english

Lost Rivers of Toronto Project. “Spadina Avenue & Chinatown West.” Accessed April 11, 2023, https://www.lostrivers.ca/content/points/spadinaave.html.

Migwans, Mikinaak, Maria Hupfield, and Syrus Marcus Ware. “Monuments, Movements, and the Photography of Jeff Thomas.” Discussion recorded on September 10 2020 at the Art Museum, University of Toronto. https://artmuseum.utoronto.ca/virtual-spotlight/monuments-movements-and-the-photography-of-jeff-thomas/

Sandra Styres, “Literacies of Land: Decolonizing Narratives Storying and Literature,” in Indigenous and Decolonizing Studies in Education Mapping the Long View (Routledge, 2019), 24-37.

Springgay, Stephanie and Sarah E. Truman. “Research-Creation Walking Methodologies and an Unsettling of Time,” in International Review of Qualitative Research 12, No.1 (2019): 85-93.

Talking Treaties Collective. “Peoples of This Land.” Accessed April 11, 2023. https://talkingtreaties.ca/peoples-of-this-land.

Thomas, Jeff. “Ground Zero: The Bear Portraits,” in Photography and Culture 10, No. 2 (2017): 181-192.

Turner, Camille. “Miss Canadiana (2001-2019).” Accessed February 9 2023. https://www.camilleturner.com/miss-canadiana

Turner, Camille. Miss Canadiana’s Heritage and Cultural Walking Tour: The Grange (2011), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UmVN270Libc.

Turner, Christina. “From Ishpadinaa to Ogimaa Mikana: Teaching Indigenous Literatures Online in Toronto,” Studies in American Indian Literatures 34, No. 1-2 (2022): 206-207.

___________________

Cason Sharpe is a writer currently based in Toronto. His fiction and criticism have appeared in Canadian Art, C Magazine, Public Parking, In The Mood Magazine, Brick, PRISM International, and the Hart House Review, among others. His first collection of stories, Our Lady of Perpetual Realness, was published by Metatron Press in 2017. Named a Queer Writer to Watch by THIS Magazine, Cason has presented work at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Vancouver Art Book Fair, the Prairie Art Book Fair, and the Hamilton Film Festival.